While double-glazed windows do help save energy, Singaporean scientists have tweaked the concept to make it even more effective. Instead of leaving an air gap between the two panes of glass, th e researchers have inserted a heat-absorbing, light-blocking liquid.

e researchers have inserted a heat-absorbing, light-blocking liquid.

Developed at Nanyang Technological University, the experimental new “smart window” consists of two panes of ordinary glass, the space between which is filled with a solution consisting of a proprietary hydrogel, water, and a stabilizing compound.

During the day, as sunlight passes through the window, the liquid absorbs and stores that light’s thermal energy. This keeps the room from heating up, reducing the need to run the air conditioning.

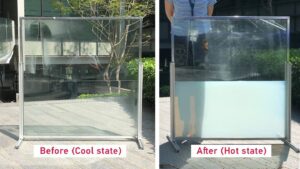

Additionally, as the liquid warms up, the hydrogel within it changes from a transparent to an opaque state. Although this ruins the view out of the window, it also reduces the amount of visible light that passes through from outside, further helping to keep the room cool.

Before and after photos of one of the smart windows, the bottom half of which incorporates the new technology. Nanyang Technological University

When the sun goes down at night, the gel cools and becomes clear again, releasing the stored thermal energy. Some of that energy passes through the glass and into the room, reducing demands on the building’s heating system.

And as an added bonus, the smart window reportedly absorbs exterior noise 15 percent more effectively than traditional double-glazed windows.

Based on simulations and real-world testing, it has been determined that use of the windows could reduce energy consumption in office buildings by up to 45 percent. The university is now looking for industry partners to help commercialize the technology, which is described in a paper that was recently published in the journal Joule.

Based on simulations and real-world testing, it has been determined that use of the windows could reduce energy consumption in office buildings by up to 45 percent. The university is now looking for industry partners to help commercialize the technology, which is described in a paper that was recently published in the journal Joule.

Scientists at Britain’s Loughborough University have been working on a similar system, although theirs utilizes plain water. Once that water has been heated by the sun, it’s pumped out of the window and stored in a tank. At night, the warm water is then pumped out of the tank and into pipes in the walls, heating the interior of the building.

Author: Ben Coxworth, November 05, 2020, New Atlas